Introduction

Icons of Devotion: Jain Artefacts in the Lahore Museum

The Lahore Museum, popularly known as Ajaib Ghar, or "House of Wonders': is one of Pakistan's oldest and most significant cultural institutions. It houses world~class collections that showcase the material heritage of Lahore and the wider region, dating back to prehistoric times. While the museum's renowned collections-such as Indus Valley artefacts, Gandharan sculptures including the iconic grey schist Fasting Buddha, and exquisite Mughal and Pahari paintingshave long attracted global scholarly interest and public admiration, its galleries are also home to countless lesser~known but invaluable objects. These artefacts silently sit in Ajaib Ghar's vitrines and corridors, waiting for a keen eye to uncover their histories and retell stories of their past lives. One such collection, often overlooked by visitors, comprises a remarkable array of Jain artefacts. Displayed in two separate locations within the museum, these objects remain hidden in plain sight; however, despite their significance, they draw little public attention. Created in the service of Jainism, one of South Asia's oldest living religious traditions, some of these pieces date as far back as the tenth century, while others bear inscriptions placing them in the early 1900s.

The 24th and last Jain Tirthankara, Vardhamana Mahavira (c. 599- 527 BCE), a slightly older contemporary of Gautama Buddha, is credited with formalising Jain doctrine. While Jainism shares several tenets with Buddhism, it is uniquely grounded in three core principles: ahimsa (non~violence), aparigraha (non~possession or non~attachment), and anekantavada ( the doctrine of manifold perspectives or multiplicity of viewpoints). Together, these principles constitute not only a rigorous soteriological discipline aimed at individual emancipation from the cycle of birth and death (samsara), but also a profound ethical framework with enduring relevance. Articulated through the lifelong practices and teachings of twenty~three earlier Tirthankaras and brought to culmina~ tion by Mahavira, this lineage systematised the Jain dharma into a coherent ethical and metaphysical system.

Though largely absent from Pakistan's public consciousness today, Jain communities once flourished across the Punjab, extending as far south as Nagarparkar in Sindh, where they played a vital role in trade, philanthropy, and civic life. A wealth of surviving structures-temples, shrines, and associated artefacts now housed in various museum collections-bear witness to a rich legacy of local craftsmanship and inter~communal exchange. Among the most prominent figures of this era was Shri Atmaram, a revered 19'h~century Jain acharya whose samadhi still stands in Gujranwala, and whose associated ritual objects form an important part of the museum's holdings today.

The patronage provided by the Gujarati Oswal merchants and lay followers from across South Asia-whose donated objects now reside in the museum's collection-speaks to a vibrant network of diasporic ties. These connections between the Punjab and major Jain centres like Gujarat reveal a transregionalJain identity, one that intricately wove together mercantile ethics, religious devotion, and aesthetic patronage across South Asia.

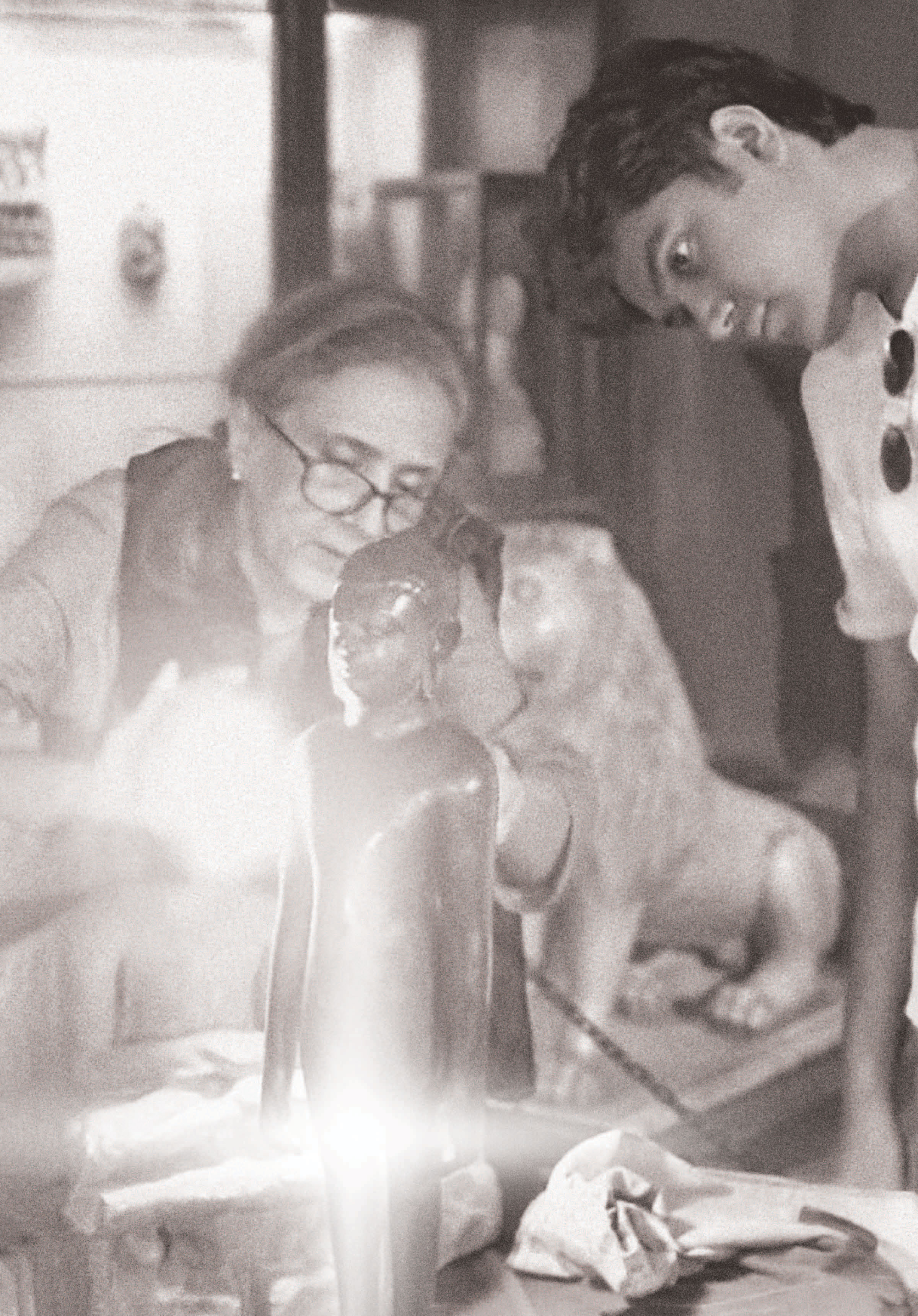

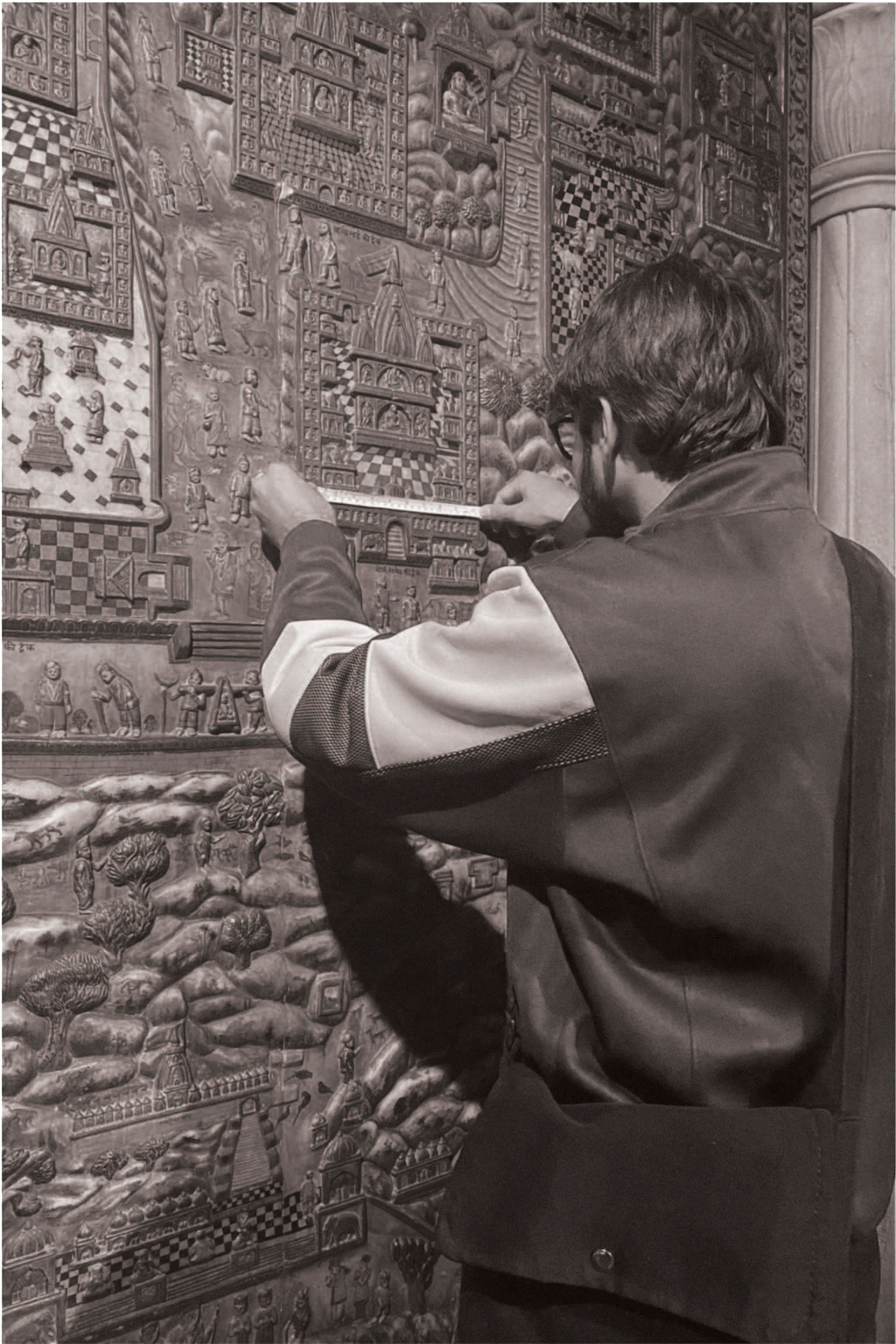

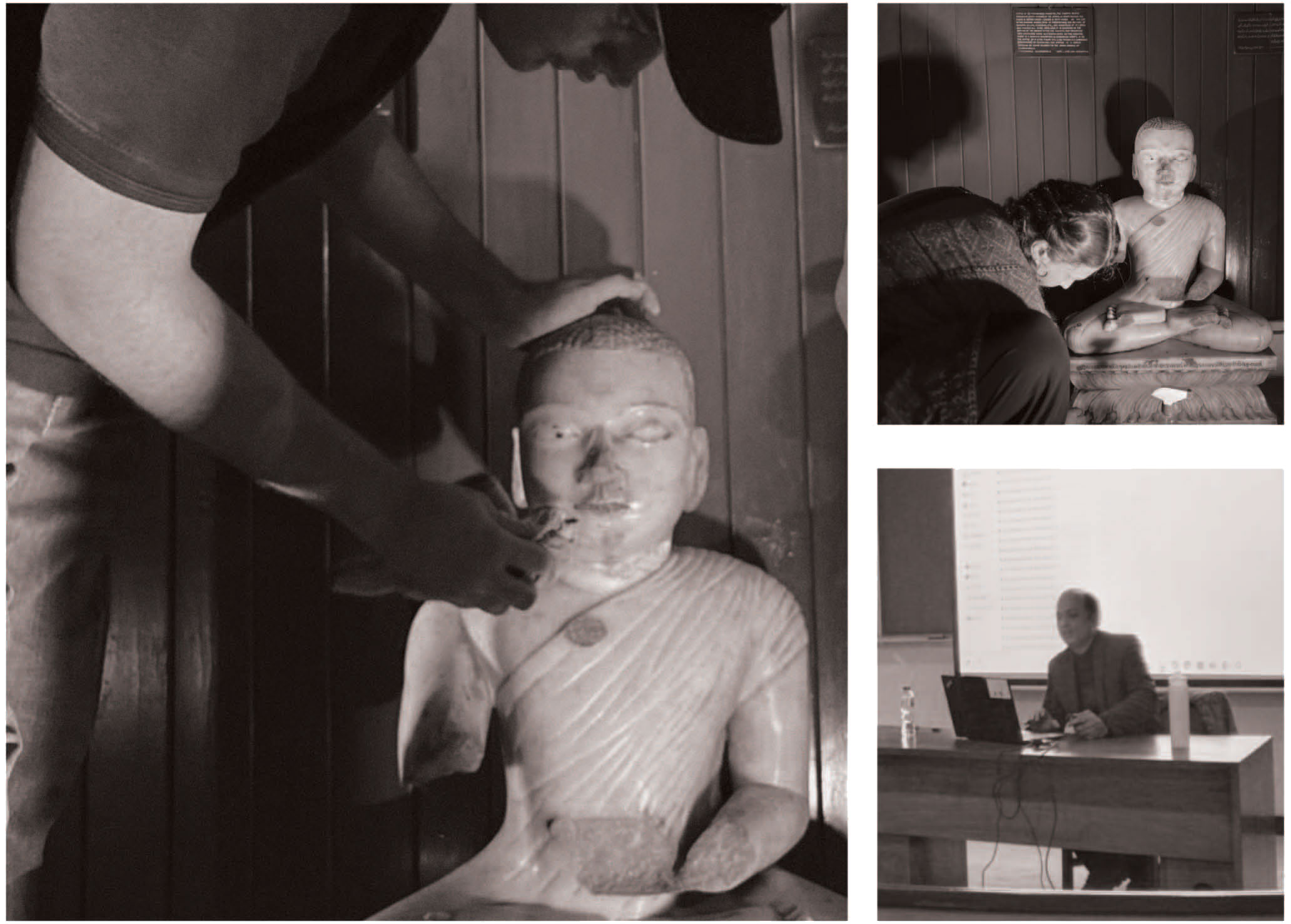

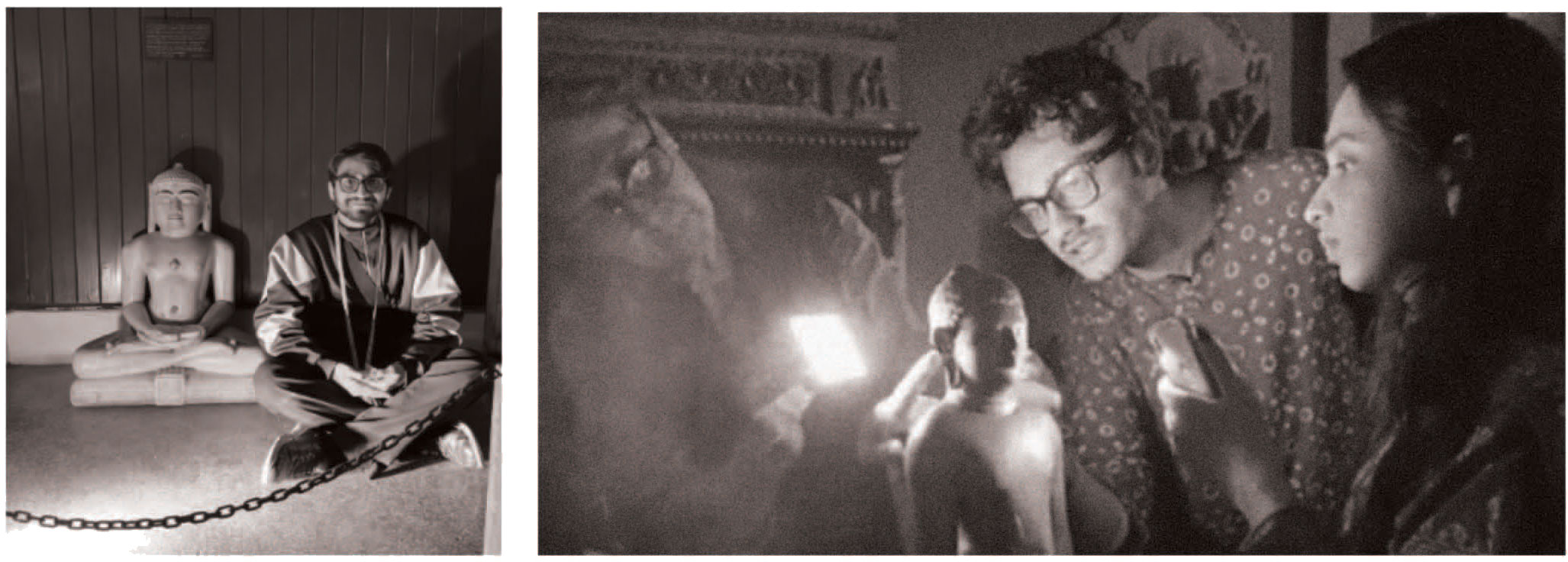

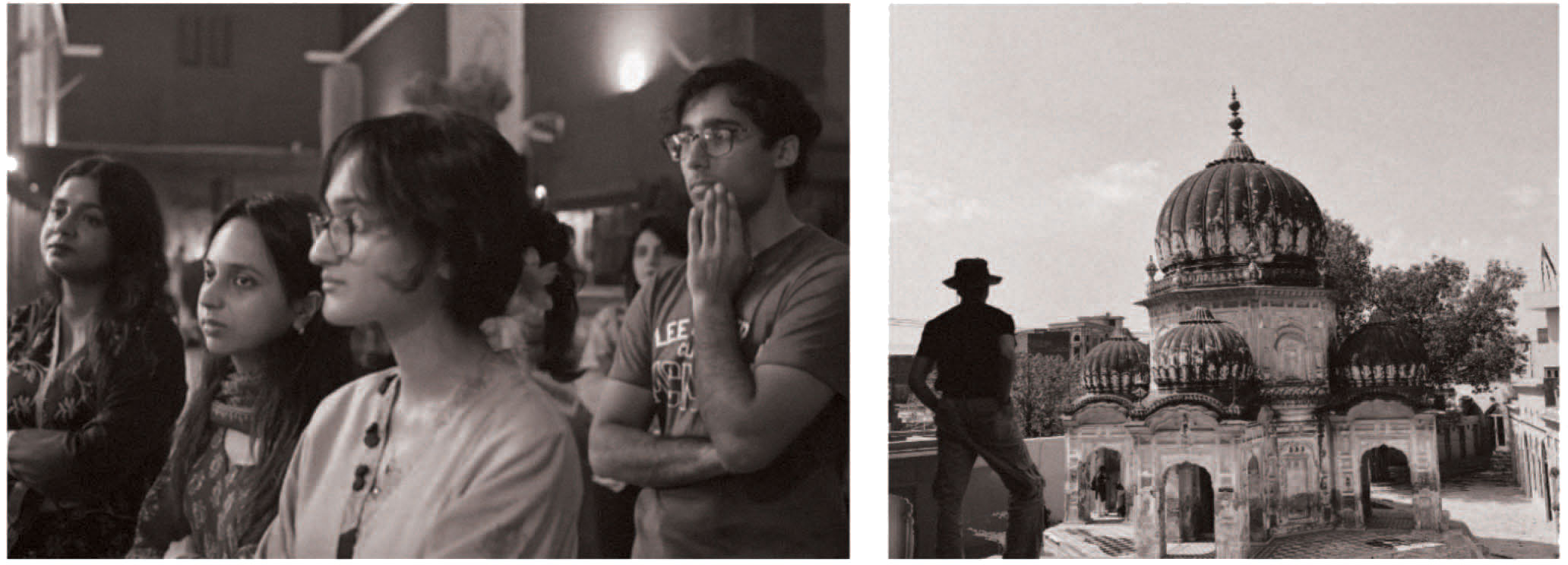

In Spring 2025, after securing formal permission from the Lahore Museum, I designed and taught an undergraduate art history seminar course "Curating Artefacts: Studying Lahore Museum's Jain Collection" as a History Department offering at the Lahore University of Manage~ ment Sciences (LUMS). As soon as the session started, a dedicated cohort of undergraduate researchers immersed themselves in a truly experiential curriculum including intensive archival workshops led on~ site by the museum curator, investigative inspections of each object in search of their identifying markers, and epigraphic decipherment sessions supervised by Jain Studies scholars. Students measured iconometric proportions of the museum's sculptures, audited provenance records in the registrar's vault, and mapped each object onto its wider ritual geography through guided field visits to local Jain pilgrimage sites. This sustained engagement with museum authorities-registrars, curatorial staff, and conservation teams-not only yielded the first critically researched labels for the Jain gallery, but also forged a new model of pedagogy in which the museum ceases to be a passive display space and becomes, instead, a living laboratory of co~learning, collective interpreta~ tion, and mutual scholarly exchange.

In an era defined by ecological crisis and societal upheaval, the rediscovery and exploration of the Jain principles of ahimsa, apari~ graha, and anekantavada have been particularly relevant. At LUMS, where students are encouraged to critically examine such ideas, this discussion centres humanity's relationship with the environment and patterns of consumption-framed both by the urgent realities of the present and by the proximity of these concepts to our own cultural and religious traditions. Approached through a rational, analytical lens, these Jain traditions are reinforced not as prescriptions for living, but as part of South Asia's rich intellectual heritage. This inquiry is situated within a broader commitment to decolonizing collections, narratives, and museological practice, thereby acknowledging the historical circumstances of acquisition and rethinking how such objects are interpreted today. By placing these ideals in dialogue with other philosophical and cultural frameworks, and by using them to provide deeper context for artefacts, this research positions LUMS as a space where heritage is not only preserved and studied, but also interrogated and reimagined-fostering critical engagement, pluralism, and a deeper understanding of the region's diverse pasts and their relevance to the contemporary world.

This catalogue, complete with a glossary and select bibliography, is but one element within a broader constellation of deliverables reaped from the Curating Artefacts course: bilingual object labels that will replace the existing ones in the museum; object reports that map each sculpture onto global analogues; thematic essays exploringJain philosophy, colonial collection practices, and postcolonial museology; richly illus~ trated digital archives and QR code~linked short films; and visionary proposals for immersive, community~led exhibitions and pedagogical workshops. Together, these outputs form an integrated research ecosystem-a scholarly resource, a pedagogical tool, and a mani~ festo-that invites us to dismantle inherited narratives, to allow contradictions to create productive tension with a pinch of rever~ ence, and to allow these artefacts to resonate across languages, traditions, and temporalities.

As you turn these pages, you will bear witness to the layered histories enshrined within marble and wood: the ascetic rigour and cosmic symbolism of lakshanas; the colonial circuits that displaced and reclassi~ fied; and the contemporary interventions of student curators who dared to listen more closely to these silent Jinas-these icons of devotion, enlightenment and emancipation. In doing so, this catalogue affirms a fundamental proposition: that curation is not mere display but an argument, an ethical gesture that may yet awaken new imaginaries of pluralism and care in our shared cultural commons. This catalogue thus emerges as an act of reclamation and resonance: to recover these sculptures from the silences of colonial and nationalist museology and to resituate them within the rich archive of Jain material culture in South Asia.

-Nadhra Shahbaz Khan

Dr. Nadhra Shahbaz Khan is Associate Professor of art history at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan. A specialist in the history of art and architecture of the Punjab from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century, her research covers the visual and material culture of this region during the Mughal, Sikh, and colonial periods.